Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

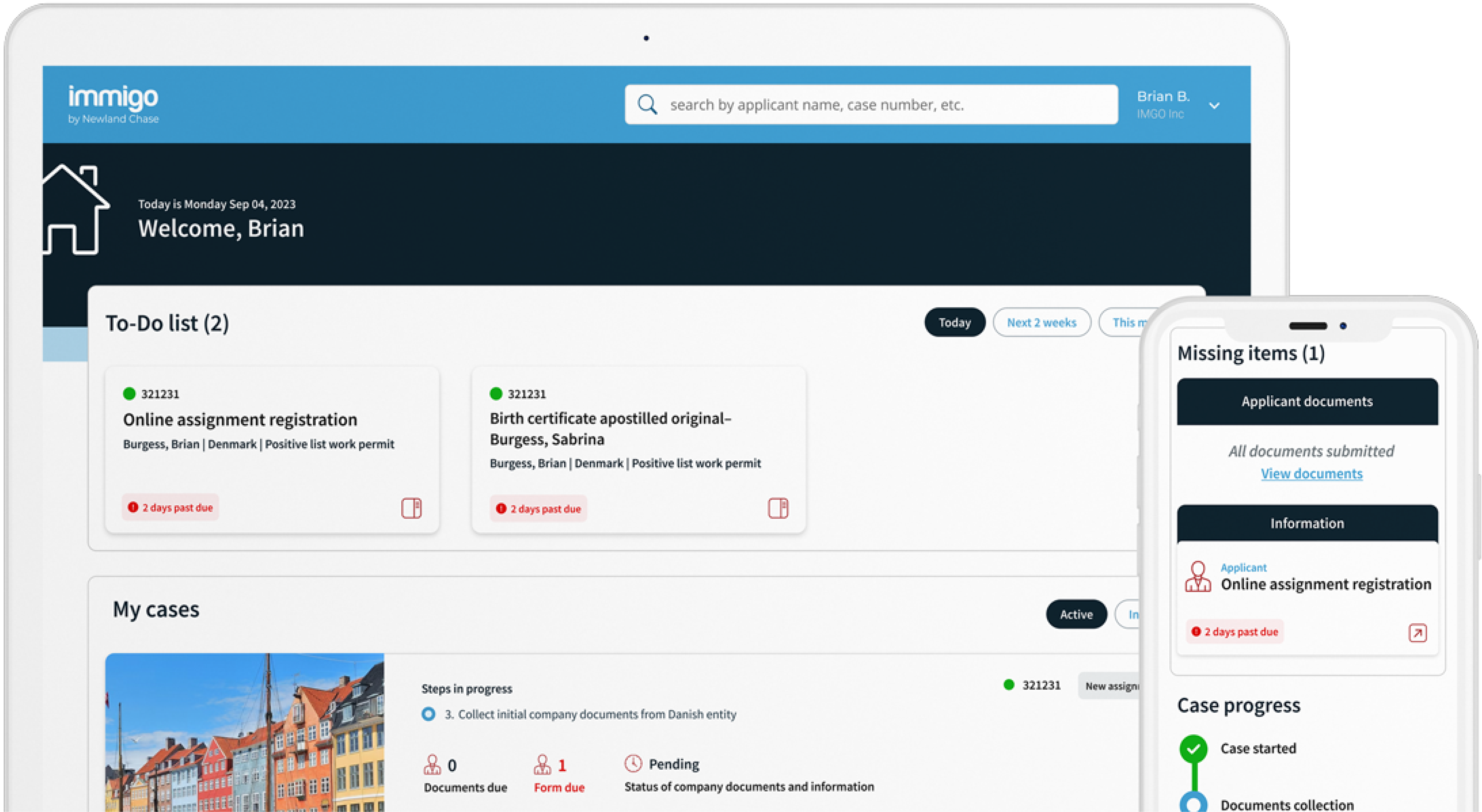

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Do I Have a “Posted Worker”?

February 20, 2019

Part I of a Two-Part Series

By Kent O’Neil

Over the last several years, “Posted Worker Rules” have become a hot topic of discussion in the European mobility industry and an oft-confusing headache for company HR and mobility managers with employees in Europe. Much of what is written on the subject focuses on the compliance requirements of equal pay and employment conditions, “posted worker notifications”, documents to be retained, and appointing company liaisons and representatives, and the intricacies of social security coverage.

But before we get to all that – Just what is a “posted worker”? This fundamental and deceptively simple question is sometimes given short shrift. However, the answer to that question is the linchpin upon which the compliance requirements hang. If I have a “posted worker”, I must file the notification, retain certain records, appoint a representative, etc. If my employee does not fall under the definition of “posted worker”, the specific posted worker requirements do not apply. For a quick summary of posted worker requirements, see EU Posted Worker Requirements… in 5 Minutes.

Therefore, for the purposes of this week’s blog, I’m setting aside the “how-to” of compliance and just focusing on the “who” of posted workers.

Background

First, some quick background. To date, there are actually three European Union directives, oftentimes referred to collectively as the Posted Worker Directives. The Posted Worker Directive 96/71/EC was the first to specifically address “posted workers” and attempt to clarify protections for workers temporarily working in EU member states other than that of their usual place of work. The goal was to ensure that companies provided their workers with the minimum applicable standards of working hours, pay, annual leave, health and safety, and other legal protections and equal opportunities.

Recognising a lack of uniformity in the way the Directive was being implemented and enforced throughout the various EU member states and to prevent potential abuse and circumvention of the rules, the earlier directive was followed by the Posted Worker Enforcement Directive (2014/67/EU). This second directive clarified what provisions the member states were to have in place in order to ensure that the worker protections of the first directive were being provided. It addressed particulars such as notification to local authorities prior to the posting, record retention, and appointment of local company representatives.

In July 2018, the EU enacted an additional directive (2018/957/EU) revising the previous Posted Workers Directives and further reinforcing the principle of “equal pay for equal work” between posted workers and local employees. The latest revision defines postings as a maximum of 12 months (extendable for another six) and calls for stricter rules regarding remuneration, temporary agency, and long-term postings. The various EU member states are to transpose these latest changes into their national laws and bring them into full effect by July 2020.

Do I Have a “Posted Worker”?

The Posted Worker Directives define “posted worker” as:

“A person who, for a limited time, carries out his or her work in the territory of an EU member State other than the state in which he or she normally works.”

At first blush, the definition appears simple enough. However, as you break it down into its components and apply them to the messy real world of cross-border assignments, that simplicity tends to fade.

“Person” – While many associate “posted workers” as EU citizens from low-wage states who are sent to perform work in higher-wage states, the definition is obviously broader than that. “Persons” referred to in the definition can include individuals employed in any European Economic Area (EEA) state or Switzerland who is temporarily working in another EEA state or Switzerland. While under EU freedom of movement principles, immigration and visa requirements may not apply – posted worker requirements can still apply. So the fact that an individual does not require a visa or work permit, does not exempt them from posted worker requirements. For example, Switzerland applies posted worker notification requirements in lieu of work permits for postings of up to 90 days.

Note that “persons” include both EU/EEA citizens as well as non-EU/EEA citizens who normally work in one EEA state temporarily working in another EEA state. Nationality of the worker is not relevant. For example, an Indian national employed in France who is sent by his employer to work in Germany for two months falls under the posted worker requirements in Germany.

“For a limited time” – The latest directive on posted workers enacted in 2018 sets an upper limit on the duration of work assignment to which the posted worker requirements apply – 12 months, but extendable for another six months. Therefore, if the worker’s temporary assignment is for more than 18 months, he or she is no longer a “posted worker”.

However, the directives themselves do not define a minimum threshold of assignment duration for posted workers. Unless a particular member state establishes a clear de minimis assignment length under which posted worker requirements do not apply, assignments even of a single day may fall under the definition. For example, authorities in Ireland are currently taking the position that since there is no clear minimum assignment length in the Directives, even assignments or visits for a single day may trigger their posted worker notification requirement.

“Carries out his or her work” – The directive specifically identify three types of assignments that are considered to be posting and thus under the purview of the requirements:

- Intra-company transfers;

- Workers at client sites; and

- Workers at temporary employment agencies.

However, setting out those three in no way limits the scope of the definition. There may be other assignments to which the posted worker requirements apply as well.

Because the definition clearly anticipates “work”, entering another EU member state for “business” should not implicate the posted worker requirements. However, as many readers are aware, the definitions of “work” and “business” and how they are applied across Europe and among governmental agencies can vary greatly. While traditional business meetings are most often considered “business” and not “work”, some authorities (e.g. Ireland) are applying posted worker requirements to business meetings even for visits as brief as one day in-country. Grey areas such as providing services in conjunction with the sale of a product are even more likely to result in confusion on the part of both companies and governmental authorities as to whether the posted worker requirements apply.

“In the territory of another EU member state” – The 27 EU members states plus Iceland and Switzerland are covered by posted worker requirements. Therefore, if the temporary assignment is located in any of these countries, posted worker requirements may apply. It is also significant to note that Norway, while not applying a posted worker notification requirement, does require a special tax registration to be filed by the host and sending entity for some types of postings from outside of Norway.

“Other than the state in which he or she normally works” – The posted worker directives generally only apply to individuals whose normal place of work is within the European Economic Area (EEA) or Switzerland. However, complicating the issue, many adopting EU member states have expanded their national requirements for posted worker notifications to include workers sent from outside the EEA to work temporarily in an EU member state as well. For example, a worker normally employed in Canada sent to work in France for two months may also be required to file a posted worker notification under the French rules.

On the other hand, there is one clear bright-line here: posted worker requirements do not apply where an employee in one EU member state takes employment in another EU member state under a local employment contract. Simply taking new employment in another state does not trigger the requirements because the worker is under a local employment contract already subject to the local employment conditions.

Next week… Part II: Real World Examples

With the complexity of this week’s topic, we’ll pause here. However, watch for Part II where we will apply the definition of “posted worker” to some typical and not so typical real world examples. Stay Tuned.

Related Content:

Do I Have a Posted Worker (Part II)

EU Posted Worker Requirements… in 5 Minutes

This blog is informational only and is not intended as a substitute for legal advice based on the specific circumstances of a matter. Readers are reminded that immigration laws are fluid and can change at a moment’s notice without warning or notice. Please reach out to your Newland Chase contact should you require any additional clarification or guidance. Written permission from the copyright owner and any other rights holders must be obtained for any reuse of any content published or provided by Newland Chase that extend beyond fair use or other statutory exemptions. Responsibility for the determination of the copyright status and securing any permissions rests with those persons wishing to reuse this blog or any of its content.