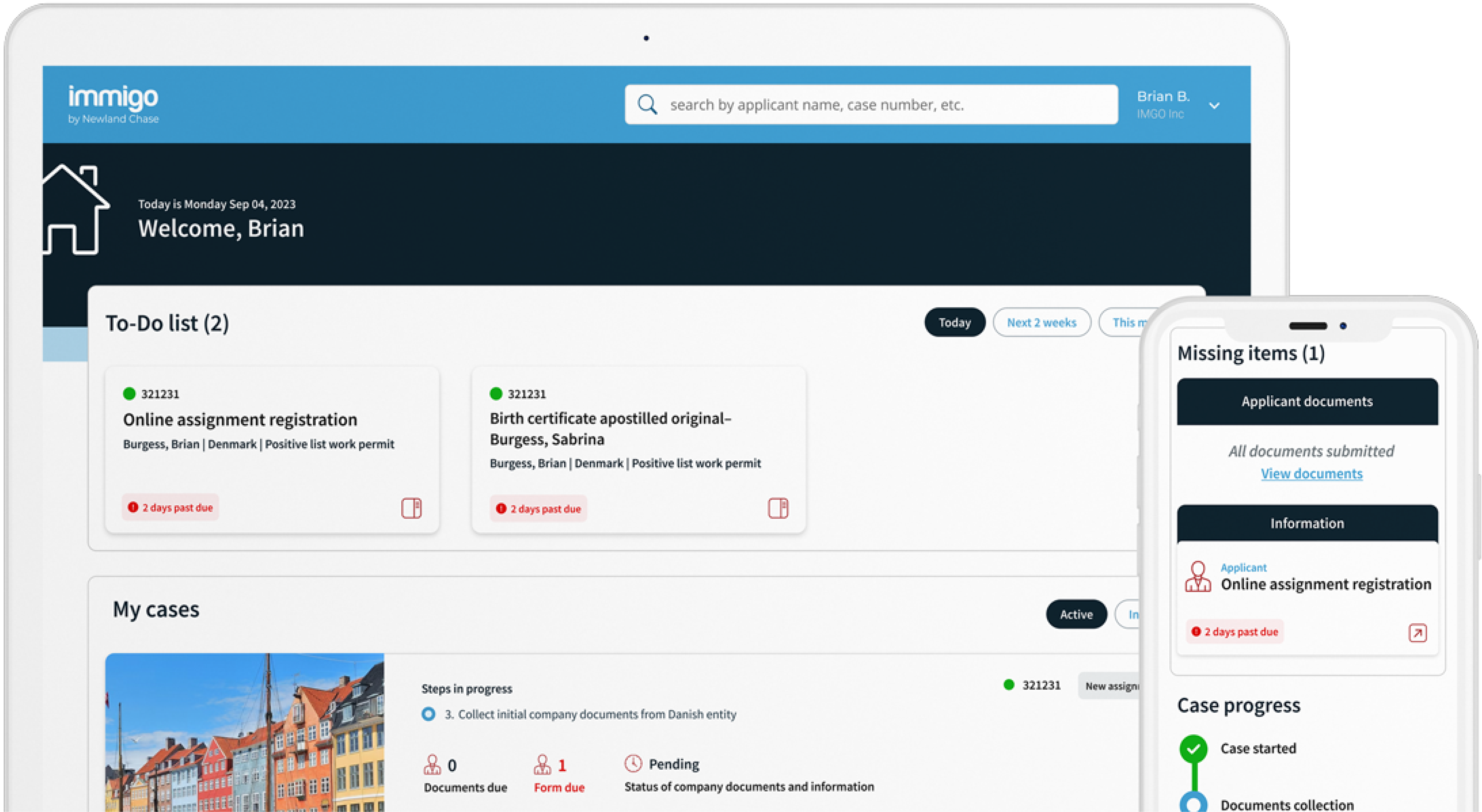

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Restrictions of rights to EEA nationals and their family members

December 13, 2013

It was just over a year ago when rights of EEA Nationals and their non- EEA family members were overhauled. The introduction of derivative right of residence with the aim of limiting rights of third country primary carers and parents of an EEA National child were fundamental with the changes reflected within The Immigration (EEA) Regulations 2006 (commonly known as the 2006 Regulations which govern the rights of entry of EEA nationals and their family members).

It was just over a year ago when rights of EEA Nationals and their non- EEA family members were overhauled. The introduction of derivative right of residence with the aim of limiting rights of third country primary carers and parents of an EEA National child were fundamental with the changes reflected within The Immigration (EEA) Regulations 2006 (commonly known as the 2006 Regulations which govern the rights of entry of EEA nationals and their family members).

In brief, derivative rights of residence provided residence options for primary carers or parents to reside with their EEA child in the UK for a period of time whilst the child is in education or is being cared for by the person claiming such residence rights. Unfortunately, it also confirmed that such parents or primary carers will never have the right of permanent residence in the UK, irrespective of how long they have been in the UK.

This time around in the Immigration (EEA) (Amendment) (No.2) Regulations 2013, the changes are aimed squarely at the ability of EEA nationals being able to claim rights enshrined within relevant EEA directive and Treaties. These changes to the 2006 regulations will have far reaching effects.

As a general rule, a person who has exercised EEA treaty rights, i.e. as a worker, can attain permanent residence in the UK after they have done so for a continuous period of 5 years. The original 2006 regulations provided means for a person to retain their status as a worker during periods of inactivity in the job market due to involuntary unemployment so long as they have been employed for at least 12 months. However, the amendments to the regulation will mean workers who involuntarily lose their jobs may only be able to retain their status for a maximum period of 6 months unless there is compelling evidence that he or she continues to seek work and has a “genuine” chance of being engage.

The second part to the change is aimed at clarifying how an A2 national may obtain permanent residence (A2 nationals are defined as Romanian and Bulgarian nationals). The change confirmed that an A2 national whom required an Accession State card to be able to claim rights as a worker, could only do so if they obtained the relevant registration documents before January 2014 and provided that the registration documents have not yet expired. Should this not have been done previously or the registration document having expired, their five year road map to permanent residence may have to start all over again.

The third part to the change provides further rights to the Home Office to “clarify” rights of an individual claiming residence under the 2006 Regulations. EEA nationals and/or their family members may be subject to an interview should the Home Office believe that they no longer have a right to reside in the UK. Although a refusal cannot be based solely on someone missing an interview, nor can it be used as a systematic method to outcast EEA nationals and their family members; it is an indicative move to restrict the rights of EEA nationals and their family members.

However, the most dramatic overhaul to the amendment is aimed at British Citizens claiming EEA Rights. Prior to this amendment, a British Citizen who had worked in another EEA member of state had the right, upon their return to the UK, to claim similar rights to those of other EEA nationals. Essentially, they could bring their spouse and children with them into the UK under EEA regulations rather than under UK Immigration Rules.

Known as the “Surinder Singh” route, this has often up to now been the preferred method for British nationals to return to the UK from other member states with their foreign national family members, due to it being easier than some of the more traditional UK visa routes.

This is particularly so since the introduction of the new spousal visa criteria, (spouse immigration rules post July 2012) as there is no need to prove a basic minimum income threshold of £18,600 and no need to prove that the foreign national spouse can speak English.

However, this will no longer be the case with the introduction of these changes to the EEA Regulations since they will introduce a “centre of life test” whereby a returning British Citizen wishing to claim the above rights must satisfy the Home Office that not only have they lived in the other member state for a period of time, but also that they transferred the centre of his or her life there. What this exactly means is unclear and undefined, but will likely be based on the length of residence in the other member of state, location of the British national’s principal residence, place of work etc.

All in all, these amendments seek to significantly restrict the rights previously enjoyed by EEA nationals and their family members, as well as British nationals who have been able to take advantage of the Surinder Singh provisions having lived in another member state. There is no doubt that the changes will attract wider judicial review or appeal from interested parties in the not too distant future.

If you have any questions regarding this blog or queries about EEA nationals’ rights please contact us.