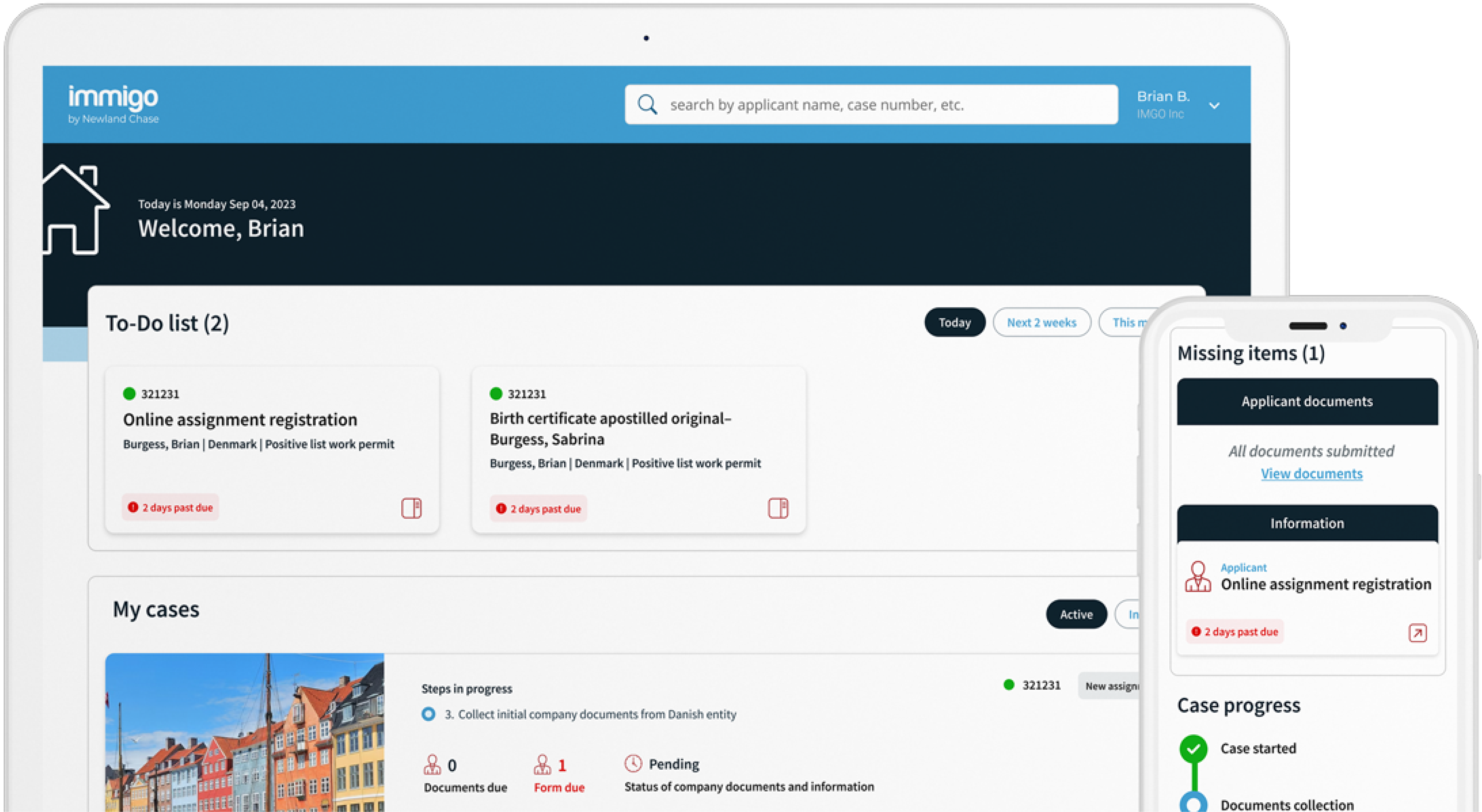

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Who Will Care?

January 20, 2012

We were pleased to read recently that the Joint Council for Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) successfully represented two Filipino care workers in their appeals against settlement refusals handed down by the UK Border Agency.

In 2007, the UK Home Office brought in new regulations governing the pay of non-EEA migrant workers in care homes. In order for non-EEA foreign nationals to be granted a UK work permit, they would now need to secure a position with a minimum hourly wage of £7.02. This caused great consternation at the time, since many care homes stated they could not afford to pay staff at these salary levels. It has always been difficult to find enough UK workers to fill these roles due to the low pay rates and the rules were clearly designed to prioritise European Union residents, encouraging nationals from A-8 countries (who had recently joined the EU) to take up the many vacancies, though this did not ultimately happen.

Currently, there are thousands of non-EEA “senior carers,” as the care workers are known by UKBA, working in homes across the UK. Many of them are from the Philippines, whose nationals are “usually very hard-working, speak excellent English, are very caring, are well qualified, and integrate very well into local communities,” as reported by the Metro. These workers were recruited abroad, brought to the UK and granted work permits by the Home Office and assured that in the future they would have access to the settlement rights available to migrants who work here legally for a period of five years (previously four years were required).

However, the UK Government altered the legal requirements for the work routes to settlement with the introduction of the Points Based System on 6 April 2011. Now, an applicant for settlement after five years’ continuous work must be earning at or above the correct minimum rate for that role, as set out in the UKBA’s Standard Occupational Classification Codes of Practice (‘SOC Codes’). It is therefore a legal requirement that senior carers earn £7.02 per hour throughout the entire duration of their five years working in the UK, and can provide evidence in the form of payslips and bank statements to this effect, or their settlement application will be rejected.

It is a sad truth, however, that many care workers are not being paid the required £7.02 per hour minimum wage. Many care homes simply cannot afford to pay their workers at this rate, and many have protested that the minimum salary is simply too high. The national minimum wage for the UK as stipulated on the Government’s website is only £6.08 per hour for workers aged over 21, which is clearly significantly lower and it seems unreasonable to expect care homes to pay non-EEA migrant workers more than the local work force.

JCWI reported that they have been acting for a number of these senior carers whose settlement applications were refused since April 2011 due to the changes to the Immigration Rules. They have just been successful in two appeals and hopefully this is a sign of how these proceedings shall continue!

JCWI summarised the grounds on which these appeals succeeded as follows:

“Firstly, the Tribunal held that SSHD’s decision to refuse settlement on the basis of the new income threshold was unlawful on Pankina grounds. In short, the income levels contained in the codes of practice imported substantive criteria into the Rules. This was exactly what Pankina considered impermissible.

Linked to the above, we argued that there was a breach of legitimate expectation. When the Appellant first came to the UK as work permit holder, she had understood that provided she remained in work permit employment, doing the same or similar work under similar conditions, she would be in a position to apply for settlement. There was no suggestion at that time that she would need to earn a particular wage.

In relation to Article 8 ECHR, it was accepted that Article 8 ECHR was engaged and that there would a breach in the light of the frustration of the Appellant’s legitimate expectations- the decision could not be in accordance with the law. Even if this was incorrect, policy points we had raised about the new threshold being a backdoor means of bringing in the skills threshold NVQ3/SVQ3 (the revised salary was linked to that skill level) had been waived for care workers could be taken into consideration in proportionality arguments.”

We hope that the Government will take notice of these cases and consider adapting its policies so that people who provide important services to the UK, working in positions which the indigenous population will not fill, are appreciated and given the settlement rights they were promised – which they richly deserve.