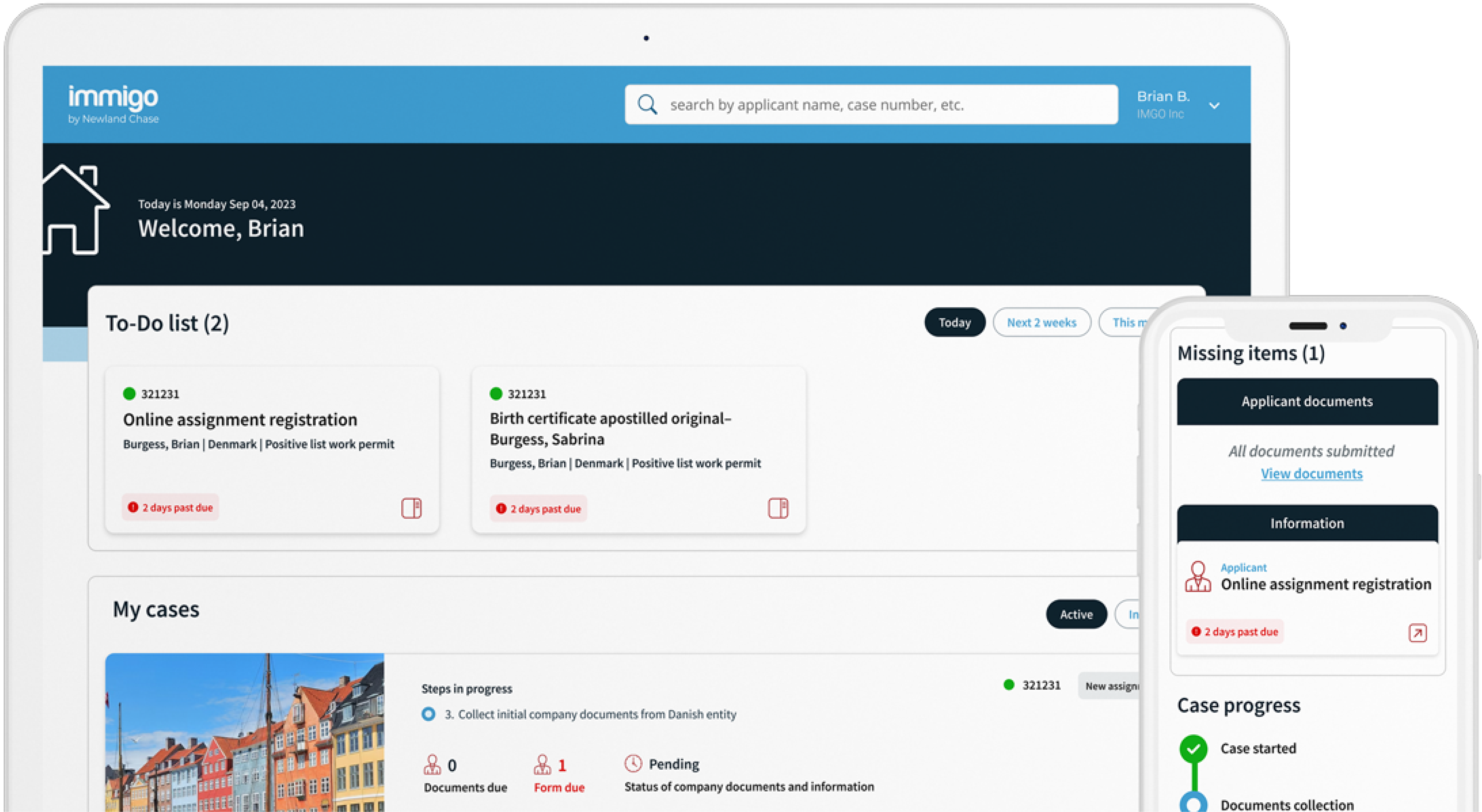

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Do you know what ‘Statelessness’ means?

December 9, 2011

This week, we came across an extremely interesting report on a subject that is unheard of by many of us in the UK. Asylum Aid and the UN Refugee Agency published a joint research report: ‘Mapping Statelessness in the United Kingdom.’ What is statelessness you may ask? Surely everyone belongs to a country somewhere? Well, perhaps shockingly, this is not the case.

The UK is one of 37 States that have ratified both the 1954 Convention on the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. ‘Statelessness’ was defined by the 1954 Convention as “a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law.” These are people who are left without legal residences, protection from embassies or consulates and have no right to return to the country they were born in, or remain in the country they have entered. The Conventions were formed to manage the status of these stateless people, and find solutions to this complex problem.

The recent report (the first of its kind) aimed to ‘map the number and profile of stateless persons in the UK’ and examine our government’s obligations to stateless people who reside here, dissecting the impact of current policies and practice.

This caught our attention since we deal frequently with applicants seeking to gain citizenship in the UK. Sadly, they are not always successful – so what then? This is a subject that is of a wider social importance. After all, as stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; everyone has a right to a nationality.

The report states that while the our government does meet most of its responsibilities in this area, it falls short in some, because “despite the UK’s obligations under the 1954 Convention and international human rights law, UNHCR and Asylum Aid found that stateless persons without leave to remain in the UK often go unidentified and those without leave to remain often live at risk of human rights infringements.”

We don’t intend to repeat the report in length here, but it makes compelling reading and we do urge you to have a read through it. Particularly the profile of Nischal, beginning on page 66, demonstrates how all too easy it is for people to become lost and destitute in our immigration system. Refused Bhutanese, Indian and British citizenship in succession and for various flawed reasons, Nischal had no access to the benefits available in the UK that we take for granted. He is completely reliant on friends and charity and on various occasions has found himself homeless. Surely, there is something wrong with a system which allows this to occur?

The report clearly highlights all the areas our government needs to work on, and makes recommendations (such as better collation of official data and access to Legal Aid for stateless persons) as to how this can be done. We hope that those in authority will take notice.