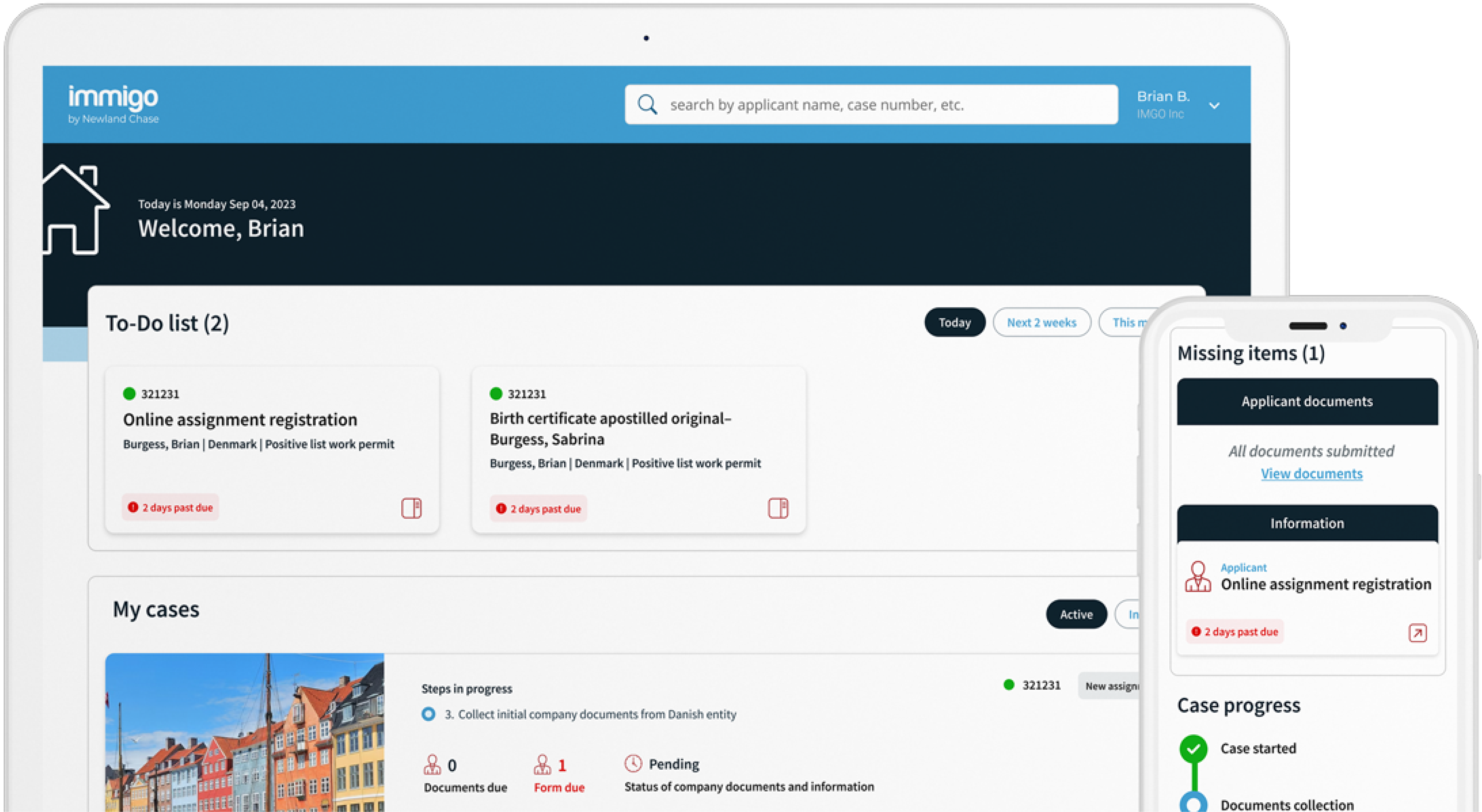

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Don’t Blame it on…Immigration?

February 15, 2012

Last week the Association of Chief Executives of Voluntary Organisations (ACEVO) published the findings of the Commission on Youth Unemployment, chaired by MP David Miliband, which carried out an investigation into UK youth unemployment (focussing on those aged between 16-24), its causes and possible solutions.

The press release accompanying the report highlighted alarming facts unearthed by the Commission, with 1 in 5 young people currently not in employment, education or training and a quarter of a million have been unemployed for over a year. The Commission points out the detrimental effect this is going to have, not only on the lives and well-being of the young people who cannot find financial security, but also on our nation’s economy which is already blighted by recession. Currently, the report states that youth unemployment will cost the public at least £4.8 billion in 2012 and £2.9 billion a year in the future. David Miliband called for immediate action, stating ‘this is a crisis we cannot afford…the crisis of youth unemployment can and must be tackled now.’

We were particularly interested to read the conclusions concerning a possible link between higher numbers of migrants in the UK and the increase in youth unemployment. There have often been factually inaccurate articles written in the press which blame migrants for today’s high British unemployment figures, accusing foreign nationals of somehow stealing UK jobs.

In fact, the report states on page 56 that ‘immigration does not appear to lead to youth unemployment. Academic research finds either no evidence that immigration results in rises in youth unemployment, or evidence that it causes a rise which could only explain a fraction of the rise in NEET [this term refers to individuals not in education, employment or training] levels in the UK between 2004 and 2008, whilst our examination of the rise in NEET levels after 2004 could find no positive link to immigration (indeed the rise in NEET levels was highest in some of the regions least affected by immigration). A further recent report by the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) found no impact from migration on claimant unemployment.’

Youth Unemployment and A8 Migrants

In 2004 the A8 countries (the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia) joined the European Union. It was feared in some quarters that this would give rise to massive numbers of A8 migrants entering the UK through the EU’s law of free movement, who would displace the native workforce.

However, the report highlights on page 118 that whilst 2004 did see a significant increase in EU migration to the UK, firstly, the NEET rate amongst A8 born 16-24 year olds remained far below the UK average. Therefore, increased numbers of A8-born 16-24 year olds moving to the UK and themselves becoming NEET could only account for between 3-5% of the overall rise in youth unemployment between 2004 and 2010.

Secondly, the report states that A8 immigration could possibly impact on the UK’s NEET rate via direct competition for jobs between A8 migrants and young UK natives – this being the favoured theory amongst the UK’s tabloid journalists. However, as the report suggests, ‘there is a large quantity of literature which finds immigration to have very limited employment effects on the native population as a whole… studies looking directly at A8 migrant flows have also found little effect; the European Commission Report in 2006 found migrants to play a complementary role in labour markets, alleviating skill bottlenecks and contributing to long term growth, whilst the International Organisation for Migration (IOM)concluded that ‘in a wide variety of western Europe, there is hardly any direct competition between immigrants and local workers.’ Furthermore, on page 119 the Commission provides a graph of the growth in A8 immigrant levels against the growth in NEET rates in the UK which shows ‘a relationship that is insignificantly different to zero.’

Clearly, then, there is substantial evidence to suggest that it is not migrants who are depriving youth in the UK of employment, but other factors which have created this predicament. The practical recommendations made by the Commission to try and address this crisis shed light on the areas in which the Government seems to be going wrong:

- Ensuring more job opportunities are available to young people in 2012: by frontloading the Government’s ‘Youth Contract’ initiative and doubling the number of job subsidies available in 2012.

- ‘First step’ – a part-time job guarantee for young people who have been on the work programme for a year without finding a job.

- Targeting young people earlier: A new national programme, Job Ready, to work with teenagers to prevent them becoming NEET in the first place. Providing localised eduation-to-career support for the non-university bound who are fast becoming the forgotten 50%.

- Youth Employment Zones: starting in the youth unemployment hotspots, local organisations should come together and pool resources to get young people into work, with Whitehall offering a turbo-boost in the form of extra freedom and flexibility in return for results.

- A new mentoring scheme for young people, by young people: where under-25s who have been in work for a year mentor others on their path to employment.

We hope that decision-makers will take notice of this report and the urgent need to address the issues facing young individuals in the UK.

However, we also hope that people will not ignore the evidence which strongly shows that we cannot continue to blame migrants for problems such as youth unemployment which are prevalent in the UK today. We must move away from pointing the finger of blame where it is most convenient and search, as this Commission has done, for real causes and solutions to these issues.