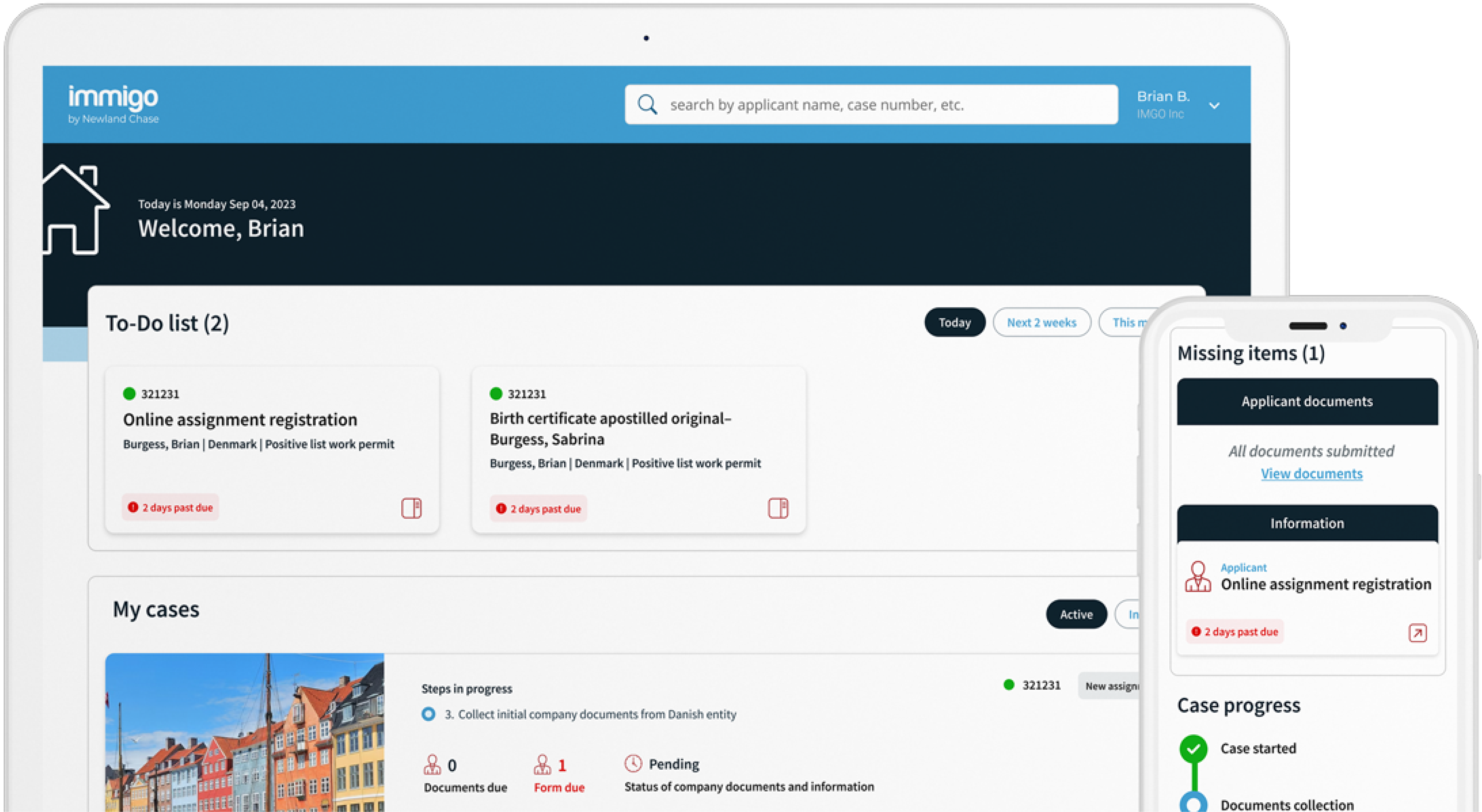

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Immigration Controls in a Pandemic: Border Control Approaches Compared

September 22, 2020

Authored by Irene Gallagher of Newland Chase Australia

In December 2019, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS- CoV-2 or COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan, China.[1] In late January 2020, China enacted a lockdown of Hubei province,[2] and the World Health Organization declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[3] By this stage, the outbreak had spread to a number of countries around the world.[4]

To contain the spread of the pandemic, countries enacted unprecedented restrictions on travel, shutting down international borders and airline routes. This article considers the border policies adopted by a sample of 50 countries, chosen at random. It relies largely on data collected by Newland Chase from in-country interviews and local publications, published on 2 May 2020 online.[5]

Countries continue to monitor and adjust their policies to respond to the ongoing pandemic, and as a consequence, the information relied on by this article may no longer accurately reflect the policies currently in place. The conclusions drawn from this analysis are intended only to provide general insight into the various approaches to border control adopted by countries around the world.

Discussion of Findings

Every country in the sample implemented some form of restriction on international arrivals, however, the extent of the restriction varied. Most countries closed their borders entirely, with exceptions for returning citizens and permanent residents, and their family members (34 out of 50 or 68%).

The remaining countries adopted a more relaxed approach to border control, either only banning arrivals from certain countries, or providing exemptions to the ban for travelers from certain countries. Eight of the surveyed countries restricted entry to visitors only from a list of specific “high-risk” countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan.

Every country in the sample implemented a quarantine or self-isolation requirement for incoming international arrivals. Generally, the quarantine requirement applied to all arrivals (with limited exceptions) for a period of 14 days, however, 14 countries in the sample (28%) imposed quarantine based on whether an arrival had visited or was a national of a certain country.

For instance, Germany exempted certain travelers from the EU and certain other European countries from quarantine,[6] while the United States only required quarantine for arrivals from China, Iran, countries in the Schengen zone, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Brazil.[7]

In addition to controlling new arrivals, COVID-19 has raised challenges for foreign nationals outside their countries of nationality. With borders closed, many countries have been faced with a significant number of foreign nationals with imminently expiring visas, who cannot be repatriated to their country of origin due to closed borders and a lack of flight services.

Most countries adopted a more lenient approach to accommodate stranded foreign nationals. From the sample of 50, 34 countries’ policies towards onshore nationals were considered.

Common policies included:

- Automatic extensions for expiring temporary visas and residence and work permits. Some form of automatic extension was adopted by 21 out of the 34 countries. This approach was particularly prevalent in European states, but was also employed in Argentina, Indonesia, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Vietnam and New Zealand. In the United Kingdom, automatic extensions applied to health workers for the National Health Service (NHS) only.[8]

- Concessions relating to extensions. 12 countries relaxed their extension policies, allowing foreign nationals who could not return home to apply for extensions of stay. These policies typically applied to temporary visa holders in countries that did not implement automatic extension.

- Reduced or suspended penalties for expired visas and permits. Nine countries had an identifiable formal policy of reducing or removing penalties for overstaying visas and not enforcing strict compliance of visa These countries included China, Denmark, Russia, Taiwan and the United Kingdom.

- Extended or altered administrative processes. Eight countries had an identifiable formal policy of extending or suspending requirements such as biometrics, medical examinations, in- person interviews and/or police

- Concessions on work restrictions. Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, who impose work restrictions on certain visas, relaxed these For example, in New Zealand, students are generally confined to 20 hours work per week, but were allowed to increase those hours if they worked in an essential service.[9]

As of May 2020, border restrictions and quarantine periods began to ease. In Europe, countries began implementing bilateral and multilateral “travel bubbles” for countries with similar risk profiles. Notably, the Baltic States of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia permitted travel within their “bubble” from 15 May 2020.[10] Austria opened its borders to some neighboring countries from 4 June 2020 and lifted restrictions to most EU countries on 16 June 2020 for persons with a medical certificate.[11]

Italy reopened its borders for tourists within Europe as of 3 June 2020,[12] and the European Commission published a recommendation that Schengen Zone countries lift internal borders from 15 June 2020,[13] which is set to be adopted by countries including Germany and Switzerland.[14] The effects of this increased international mobility on the spread of COVID-19 remains to be seen.

Lessons for the Future

This sample indicates that countries adopted broadly similar approaches to containing COVID-19, and travel bans were a particularly prominent response. In their study, Wells et al found that airline connectivity with mainland China correlated significantly with increased COVID-19 risk in the early stages of the pandemic.[15] Stricter border controls therefore potentially reduce incidences of COVID-19; a hypothesis that appears to be supported by comparing the United States, United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand.

Between 31 January 2020 and 14 March 2020, the United States restricted entry for foreign nationals who had been in China, Iran and certain European countries in the 14 days prior to travelling to the United States.[16] Citizens and residents returning from these countries were required to go through enhanced airport screening and self-quarantine for 14 days.[17]

The United Kingdom similarly opted to restrict entry based on travel history, and imposed quarantine requirements for international arrivals much later on 8 June 2020.[18] Both these countries have become major hotspots for the disease.

As of 11 June 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the United States had 1,994,283 reported cases of COVID-19 (20,486 new cases in the past 24 hours) and 112,967 deaths[19], while the United Kingdom reported 291,409 confirmed cases and 41,279 deaths.[20]

By comparison, Australia and New Zealand had measures in place from early February and implemented complete entry bans from 20 March 2020 with limited exceptions for returning citizens, residents and their families.[21] As at 11 June 2020, the Australian Department of Health reported 7,285 total cases (9 new cases in the last 24 hours) and 102 deaths.[22] The New Zealand Ministry of Health reported 1,154 confirmed cases, and as at 11 June 2020 had reported no new cases in the preceding week.[23]

These comparisons should be read with caution, as infection and death rates represent an unreliable metric due to different counting methods, levels of testing and other variables.[24] Nevertheless, there appears to be a disparity between Australia and New Zealand, who implemented a total ban, and the United States and United Kingdom, who implemented a selective ban. This disparity could be explained, in part, due to COVID-19’s long asymptomatic incubation period.

Policies that restrict travelers from “high risk” locations based on airport screening or data of reported cases rely on potentially outdated information that does not effectively account for individuals in the incubation period, who may go undetected.[25] A blanket ban avoids these difficulties.

Despite this, Japan and South Korea both adopted a selective approach to border control, and originally reported a high number of cases but have since had success controlling the spread of the virus domestically.[26] Both these countries implemented internal measures including social distancing, widescale testing and contact tracing. This indicates that while complete travel bans may delay the importation of COVID-19, it is not the only effective mechanism.

Conclusion

Countries have broadly adopted similar border policies to managing COVID-19, including implementing entry restrictions, quarantine periods and taking a more lenient approach to onshore foreign nationals who cannot return to their usual countries of residence. Despite this general consistency, the extent and success of these measures has been variable. This study has identified some correlation between the early implementation of strict entry bans and success in containing COVID-19, however, this is not necessarily a general rule.

This article originally appeared in the Lexis Nexis Australia Immigration Review.

[1] Catrin Sohrabi et al, “World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19)” (2020) 76 International Journal of Surgery 71, 71.

[2] Chad R Wells et al, “Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak” (2020) 117(13) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 7504, 7504.

[3] Sohrabi et al (n 1) 71.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Newland Chase, “COVID-19: Latest Travel and Immigration Updates” (2 May 2020).

[6] Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community, “Coronavirus: Frequently Asked Questions” (2020) <www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/faqs/EN/topics/civil-protection/coronavirus/coronavirus-faqs.html#doc13797140bodyText4>.

[7] See Proclamation No 9996 Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain Additional Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus (14 March 2020) 85 FR 15341; Proclamation No 9994 Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak (13 March 2020) 85 FR 15337; Proclamation No 9993 Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain Additional Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus (11 March 2020) 85 FR 15045; Proclamation No 9992 Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain Additional Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus (29 February 2020) 85 FR 12855; Proclamation No 9984 Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus and Other Appropriate Measures To Address This Risk (31 January 2020) 85 FR 6709.

[8] United Kingdom Government, “Visa extensions for health workers during coronavirus (COVID-19)” (Web Page, 2020) <www.gov.uk/coronavirus-health-worker-visa-extension>.

[9] New Zealand Immigration, “Covid-19: Key Updates” (Web Page, 2020) <www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/covid-19/coronavirus-update-inz-response>.

[10] Memorandum of Understanding between Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Estonia, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania on Lifting of Travel Restrictions Between Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania for Land, Rail, Air and Maritime Transport and Cooperation Thereof During the Covid-19 Crisis, signed 15 May 2020 (Memorandum of Understanding); Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia, “Travel within the Baltic States” (Web Page, 15 May 2020); Republic of Estonia Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “MoU: Lifting of Travel Restrictions Between Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania for Land, Rail, Air and Maritime Transport and Cooperation Thereof During the Covid-19 Crisis” (Web Page, 15 May 2020)<https://vm.ee/en/news/mou-lifting-travel-restrictions-between-estonia-latvia-and- lithuania-land-rail-air-and-maritime>.

[11] The Austrian National Tourist Office, “Up-to-date Information on the Coronavirus Situation” (Web Page, 2020) <www.austria.info/en/service-and-facts/coronavirus-information>.

[12] Decreto-Legge 16 maggio 2020 no 33 [Decree Law No 33 of 16 May 2020] (Italy) OJ General Seriesn. 125, 16 May 2020 <www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/05/16/20G00051/sg>; Italian Government, Presidency of the Council of Ministers, “‘Phase 2’ — Frequently asked questions about the measures taken by the government” (Press Release, 1 June 2020) <www.governo.it/it/faq-fasedue>

[13] European Commission, “Coronavirus: Commission recommends partial and gradual lifting of travel restrictions to the EU after 30 June, based on common coordinated approach” (Press release, 11 June 2020) <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1035>.

[14] Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community, “Changes in the border regime” (Press Release, 13 May 2020) <www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/EN/2020/05/changes-in-the-border-regime.html>; Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, “Coronavirus: Switzerland to reopen its borders with all EU/EFTA states on 15 June” (Press release, 5 June 2020) <www.eda.admin.ch/ eda/en/fdfa/fdfa/aktuell/news.html/content/eda/en/meta/news/2020/6/5/79365>.

[15] Wells et al (n 2) 7504, 7507.

[16] Proclamation No 9984 (n 7); Proclamation No 9992 (n 7); Proclamation No 9993 (n 7); Proclamation No 9996 (n 7).

[17] Proclamation No 9984 (n 7).

[18] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “COVID-19 and travel”, (5 June 2020) <www.smartraveller. gov.au/destinations/europe/united-kingdom>.

[19] Centre for Disease Control, “Cases in the US” (11 June 2020) <www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html>.

[20] Department of Health and Social Care and Public Health England, “Number of coronavirus (COVID-19) cases and risk in the UK” (11 June 2020) <www.gov.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19- information-for-the-public#number-of-cases-and-deaths>.

[21] Prime Minister of Australia “Border Restrictions” (Media Release, 19 March 2020) <www.pm.gov. au/media/border-restrictions#:~:text=Australia%20is%20closing%20its%20borders,spouses%2C% 20legal%20guardians%20and%20dependants.>; Jason Walls, “Coronavirus: NZ shutting borders to everyone except citizens, residents — PM Jacinda Ardern” New Zealand Herald (19 March 2020)<www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12318284>.

[22] Department of Health, “Coronavirus (COVID-19) current situation and case numbers” (11 June 2020) <www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers>.

[23] Ministry of Health, “COVID-19 — current cases” (12 June 2020) <www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases>.

[24] David Spiegelhalter, “Coronavirus deaths: how does Britain compare with other countries?” The Guardian (30 April 2020) <www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/30/coronavirus-deaths-how-does-britain-compare-with-other-countries>.

[25] Wells et al (n 2) 7508.

[26] Jake Sturmer and Yumi Asada, “Japan was feared to be the next US or Italy. Instead their coronavirus success is a puzzling ‘mystery’” (News Article, 23 May 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-23/ japan-was-meant-to-be-the-next-italy-on-coronavirus/12266912>; Vernon J Lee, Calvin J Chiew and Wei Xin Khong, “Interrupting transmission of COVID-19: lessons from containment efforts in Singapore” (2020) 27(3) Journal of Travel Medicine 1, 1.