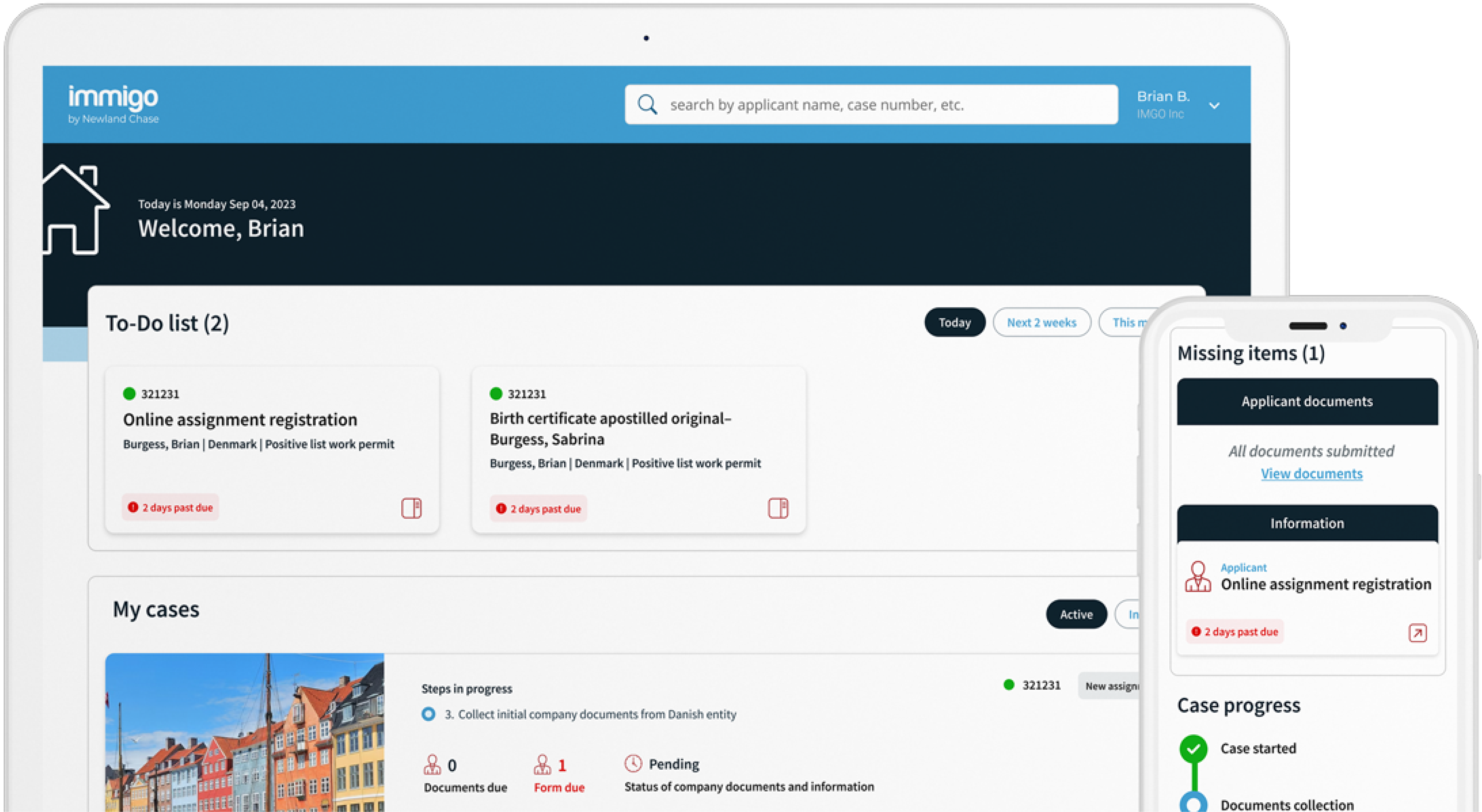

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Is the UK destroying Entrepreneurship when we need it most?

January 18, 2013

A recent article written by a Director and Professor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in America, which discussed U.S. immigration policy in respect of international students and their options post-graduation, has caught our eye and inspired us to consider whether our own policies are any more encouraging.

A recent article written by a Director and Professor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in America, which discussed U.S. immigration policy in respect of international students and their options post-graduation, has caught our eye and inspired us to consider whether our own policies are any more encouraging.

We have discussed the UK Government’s student immigration policies in a previous Newland Chase blog post and have shared our concerns on the increasingly strict and demanding nature of recent legislative changes in this area.

But what opportunities are available to foreign students after they have graduated in the UK? Are there provisions through which these graduates can set up and develop their own business initiatives, or is the only option to find a Tier 2 Sponsor or go home? And from a global perspective, how do we compare with countries such as America, Australia or Canada, with whom we are competing to recruit the most talented graduates?

In today’s blog we hope to address these questions and more…

Post Study Work in the UK – what are the options?

We still receive enquiries from international students in the UK who ask about the Tier 1 (Post Study Work) Visa. This visa allowed non-EEA graduates to search for employment for up to two years in the UK. If they found a role with a company willing to sponsor them, the graduate would then be able to switch into Tier 2 (General) of the Points-Based System.

Now the Tier 1 PSW visa category has been closed, Tier 4 students need to find employment with a Tier 2 Sponsor before the expiry of their current visa. This is causing many students to leave the UK after graduation, because there is a lack of Tier 2 Sponsors in sectors such as administrative and support services, business management, public relations, arts and recreation activities and manufacturing.

What about the options for those international students who have an entrepreneurial streak and are keen to start their own business in the UK? Does current Government policy make it easy for them to achieve this?

Under the old Highly Skilled Migrant Programme, and following closure of the HSMP category, the Tier 1 (General) provisions, it was much easier for foreign graduates to become self sufficient. We have handled many Tier 1 (General) Extension applications from individuals who graduated with a Masters in Business Administration and have since been very successful in either establishing a limited liability company or operating as a sole trader. Some of these clients have assisted with important Government initiatives and are following expansion of their companies are now seeking to recruit from the local UK workforce. Clearly, they have made significant contribution to the UK as a result of their business activities.

However, the Tier 1 (General) route is now closed to new applicants and it appears as though the options for non-EEA graduates are becoming increasingly limited. The Government has introduced the Tier 1 (Graduate Entrepreneur) visa to try and redress the balance, but how useful is this category in practice?

The Tier 1 (Graduate Entrepreneur) visa

This visa category opened on the 6th April 2012 and is described on the UK Border Agency (UKBA) website as allowing the UK ‘to retain (non-European) graduates identified by UK higher education institutions as having developed world class innovative ideas or entrepreneurial skills.’

The requirements for the Tier 1 (Graduate Entrepreneur) visa include the following:

- Students must provide a letter of endorsement from an approved UK Higher Education Institution;

- The endorsement must confirm the UK Higher Education Institution has assessed the applicant and his/her business idea;

- The UK Higher Education Institution has awarded the applicant a United Kingdom recognised bachelor’s or postgraduate degree; and

- A maintenance requirement.

This visa will be granted for one year initially and can then be extended for a further year provided the UK Higher Education Institution continues to endorse the applicant. Graduates may then apply to switch into the Tier 1 (Entrepreneur) route and will only have to demonstrate that they have £50,000 in funds to invest, rather than the standard £200,000 required.

In practice, then, how useful is this visa in assisting international students who are graduating from a UK university and want to set up a legitimate business here?

Are we really inviting ‘the brightest and the best?’

It is important to note that only 1,000 places per year have been made available on the Tier 1 (Graduate Entrepreneur) scheme for the first two years since implementation, that is, up to April 2014. Availability is therefore somewhat limited, although the reports we receive suggest that this category is in fact rather undersubscribed.

In addition, in order to qualify for the visa students must demonstrate to their university that they have ‘a genuine, credible and innovative business idea,’ which seems to suggest that a fairly sophisticated business model is required. However, it is only through trial and error at the development stages that many businesses take shape and become successful. Intelligent, enthusiastic students, who perhaps have some thoughts of the type of business they wish to create, but have not gained enough business or commercial acumen to really understand how their ideas can be effective, will struggle to produce an ‘innovative,’ detailed plan as required by the UKBA.

If a foreign student fails to procure the university endorsement, then what are his or her options for setting up a business? At the moment there seems no recourse other than to uproot and take their plans elsewhere.

How does the UK compare on the global stage?

In the excellent article which prompted this blog, the writers highlight the lack of provision in America for international students with an entrepreneurial streak. They mention the fact that when these students graduate, their only options are to take a job with a company who will sponsor them for the H-1B visa or attempt to secure a visa extension for a year of ‘optional practical training.’ After completion of the training, entrepreneurs can apply for an H-1B visa for their start-up company, provided it meets other requirements. However, the article notes that even if graduates follow this path, ‘they are not allowed to become a majority shareholder in their own startup.’

Clearly, this seems unfair. The writers point out that ‘innovation-driven entrepreneurs are the engine of a vibrant economy. Their high levels of education and their pursuit of global markets and rapid expansion create jobs and economic prosperity. And many of them, such as these MIT students, were not born in the United States.’ We agree with this statement and it was interesting to read that the UK was selected as an example of a country which is attempting to welcome entrepreneurs through the creation of specific new visa categories. But are we doing enough? It is our opinion that it more work must be done to encourage foreign graduate entrepreneurs to stay in the UK rather than venture elsewhere.

In 2010, the Australian Government commissioned a review of its student visa programme in recognition of the importance of international education to Australia’s society and economy. The report can be read here and recommendations are being currently being implemented which include the provision of post study work visas. These visas can be granted for up to four years and allow graduates to gain practical experience in Australia after completing their studies.

This approach is obviously very different to that adopted by the British and American Governments and Canada is another country which is known to welcome international students. Foreign graduates in Canada are able to apply for leave to remain under the Post-Graduation Work Permit Program (PGWPP). Through this visa they can gain work experience in Canada which will also count toward any future application for permanent residence.

Should the UK Government be examining its approach to international students and learning lessons from countries such as Australia and Canada?

The American article posed the question; ‘what if Steve Wozniak had been born not in San Jose but in Saskatchewan?’

And we’d like you to consider:

What if Richard Branson had been born not in London, but in Lagos?

Please leave your general comments and views below as we enjoy reading them all. For specific enquiries, please contact us via email or give us a call on 0207 0012121.