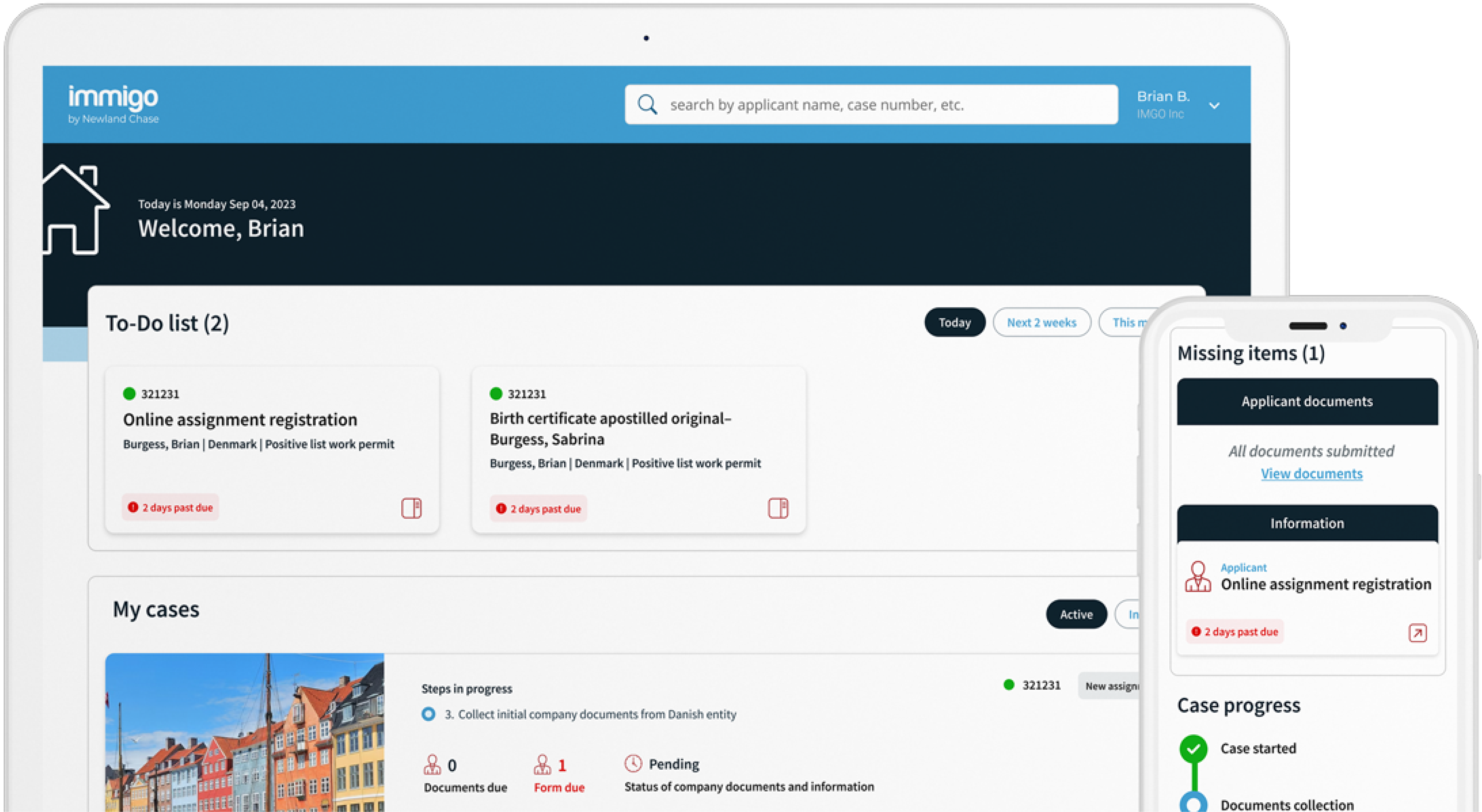

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Leaving on a Jet Plane…not without access to your lawyer first!

March 9, 2012

An important judgment was handed down recently by the Court of Appeal in the case of The Queen on the Application of Medical Justice v Secretary of State for the Home Department [SSHD] [2011] EWCA Civ 1710. The Court found that certain Government policy, which allowed for expedited removal of certain categories of applicants for permission to enter or remain in the UK, is unlawful.

The Government had lodged an appeal against the decision of the Administrative Court that applicants who make unsuccessful claims to enter or remain in the UK cannot be removed without being given sufficient time for a solicitor to prepare a challenge against their claim.

Silber J had quashed the Government policy as being unlawful because it breached the right of access to justice of those facing imminent removal. The Government policy had controversially allowed for expedited removal procedures in certain circumstances; for example, in situations where an applicant with notification of his removal may attempt to frustrate such measures.

The case focused on the Home Office’s 2012 document, entitled ‘Judicial Review and Injunctions’ which advocated a minimum period of 72 hours (including two working days) between the setting of removal direction and the actual removal procedure being put into effect, during which time an application for judicial review could be made. However, the Government had created exceptions to the 72 hour rule that allowed for the removal of unsuccessful claimants with little notice of the removal decision in certain situations; such as when a swift removal was deemed necessary to maintain order in removal centres, or if the detainee has a history of non-compliance with removal orders.

The SSHD attempted to argue that ensuring all individuals had access to a court would require them also having access to legal advice, possibly paid for by the state, which could have ‘significant implications for the provision of legal services in this country and for the availability of public funding for legal advice’.

The appellant also argued that instead of quashing the policy, the court should simply await challenges in individual cases, which Silber J had rejected as being ‘inappropriate’, as unsuccessful applicants would be deported in accordance with the 2010 exceptions and unable to pursue their claim from abroad.

It was also felt that the removal procedure could not be expedited beyond the 72 hour rule because removal directions may be delayed by the legal process itself, as the removal order could be subject to challenge under the ECHR or the doctrine of internal relocation, by which an Immigration judge might consider evidence that the person in question could be relocated to another part of the country. The business of obtaining legal advice about all this ‘cannot be short-circuited’ and usually ‘inevitably takes substantial periods of time’.

The Secretary of State’s appeal was dismissed and the ruling of the Administrative Court upheld, because unlike the 72 hour timeframe, the 2010 exceptions failed to include provisions ensuring that there was access to the courts. Even the exception for implementing removal directions within the 72 hour timeframe where the subject consented was ruled unlawful, since there was an ‘underlying concern’ that in such a very short timescale it would not be possible to ascertain whether genuinely informed consent was given, leading to ‘a very high risk that the right of access to justice is being and will be infringed’.

This is clearly an important and welcome case in ensuring that migrants who have been issued with removal directions are granted the rights and access to justice to which they are entitled. Of course, we accept that there must be a process in place for maintaining immigration control in the UK and this involves removing those who have no right to remain in the UK via legitimate means. However, we have often dealt with cases where a migrant with proper grounds for staying in the UK has been issued removal directions, but is given little or no notice of them, and therefore no time in which to assemble their case against the orders. Removing a person’s access to legal advice and assistance is a fundamental breach of human rights, made all the worse by the fact that they only have a few hours before being forced to leave the UK.