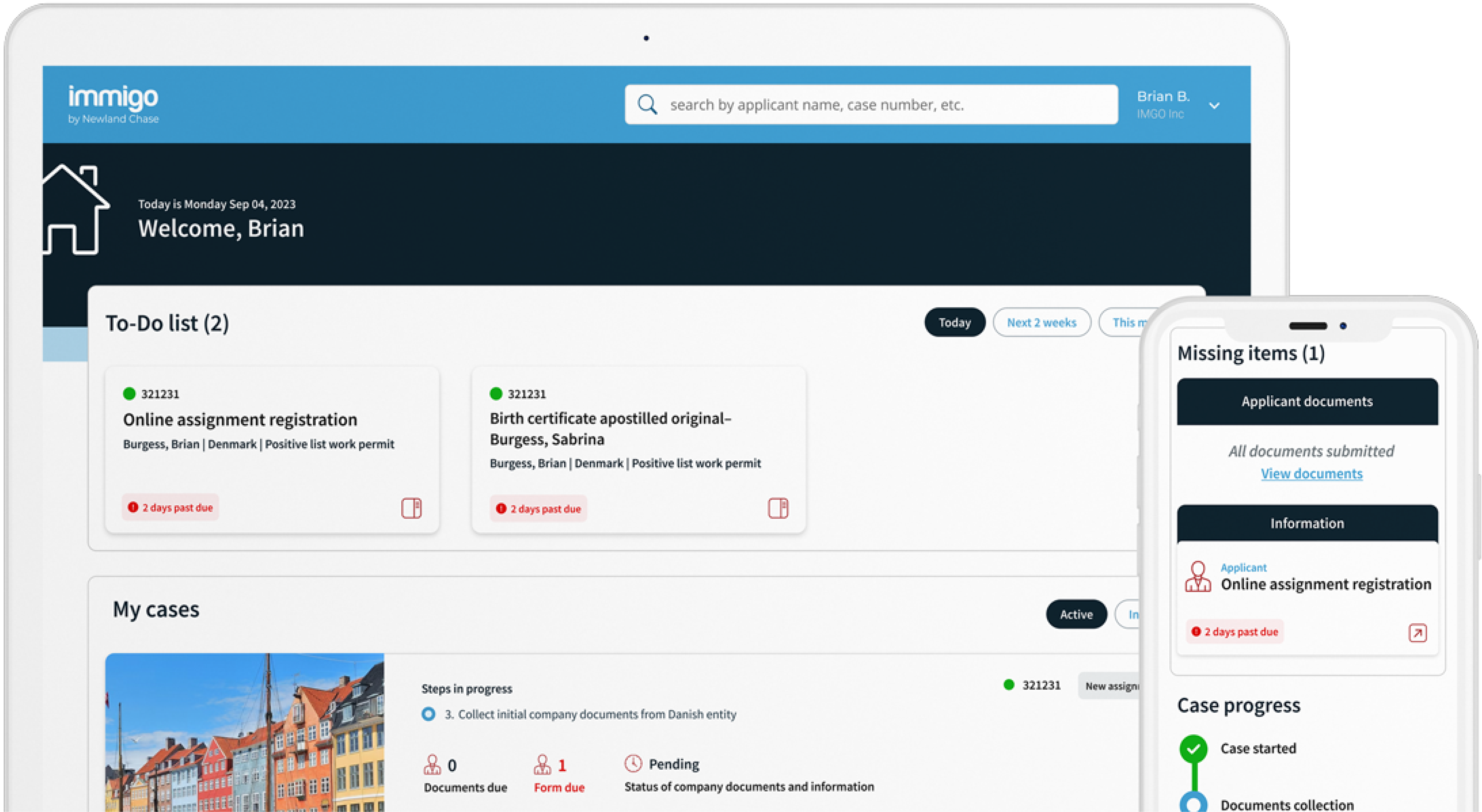

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Misconception to Article 8 Cases

November 20, 2013

We have often heard in the media that non-qualifying migrants simply need to rely on Article 8 (European Right to Respect for Private and Family life) to linger in the UK irrespective of whether they qualify under the rules. To exacerbate the situation, the media will also report that Courts will blindly accept any Article 8 claim at face value.

We have often heard in the media that non-qualifying migrants simply need to rely on Article 8 (European Right to Respect for Private and Family life) to linger in the UK irrespective of whether they qualify under the rules. To exacerbate the situation, the media will also report that Courts will blindly accept any Article 8 claim at face value.

This could not be further from the truth. Article 8 claims are generally used as a shield and not a sword. Such rights are to be used in a reasonable manner to protect people against an infringement rather than to force their stay in the UK.

Over the past decade, case law within all levels of the courts have established the correct way for the court to consider such cases. In particular, key cases such as Razgar [2004] UKHL 27 and Huang [2007] UKHL 11 established guidelines under which all Article 8 cases ought to be considered. However, no where in these cases will you find it said that Article 8 is an absolute right. Rather, it is a balancing exercise between the infringement of a person’s rights and effective immigration control and ultimately whether the interference with a person’s Article 8 rights leads to “sufficiently serious” circumstances for those concerned.

Furthermore, where a person makes an immigration application but fails to meet the rules, claiming Article 8 does not mean they can automatically stay in the UK. In fact, in most Article 8 cases considered by the courts, the Judge will state that only a minority of cases can succeed on Article 8 grounds should the applicant fail to meet the immigration rules.

The reason why only a minority of cases can succeed in this manner is because, as stated above, the interference must be “sufficiently serious”, taking into account the person’s entire circumstances.

A great example of this principle was applied in court in an unreported Upper Tribunal case this year. A Nigerian family, both parents of which are highly qualified and work for the NHS had been in the UK since 2005 and therefore in excess of 8 years. Their 2 children had become accustomed to their life in the UK.

Although the couple earned a very good living, their application fell short because the husband, who was the main applicant for the family, failed to register as self-employed and therefore failed to pay taxes in the proper manner.

An appeal was lodged suggesting that this was a minor error which could be rectified and of course an Article 8 claim was included relating to the length of time that the family had been in the UK.

The case was initially dismissed as it was clear that the family did not strictly meet the rules of the immigration category under which they were applying. However, the Article 8 claim pushed the case up to the Upper Tribunal.

The Tribunal was meticulous in assessing the family’s circumstances and weighing out the family’s contribution to British Society. Although the court agreed that the tax issue was one that was not of particular concern asit could be rectified, the court maintained that the family did not meet the requirements of the immigration rules and ultimately that returning the family to Nigeria would not be disproportionate.

The court carefully explained that although there would of course be interference to the family’s private and family life in the UK which had of course been established over a number of years t, such interference would be proportionate to ensure effective immigration control. The Upper Tribunal’s key reasoning was that the majority of the family’s upbringing and life has been in Nigeria prior to coming to the UK and since the main applicant was highly skilled, there would be no undue distress or interference for him to resettle back in Nigeria, albeit that some disruption would entail.

Therefore, to say that Judges are a soft touch on Article 8 cases is definitely untrue and this case goes to highlight that this is a popular misconception.

By the same token however, this case does not represent an end to Article 8 claims. It simply means Article 8 cannot be used as a tool to push for further stay in the UK, but must be used in the correct manner. If there is a real interference with an applicant’s private and family life and the interference is sufficiently serious, the Courts will fairly and diligently consider the claim and judge accordingly.

If the contents of this blog affects you or your family, please do not hesitate to contact Newland Chase on +44(0) 207 001 2121 for further information.