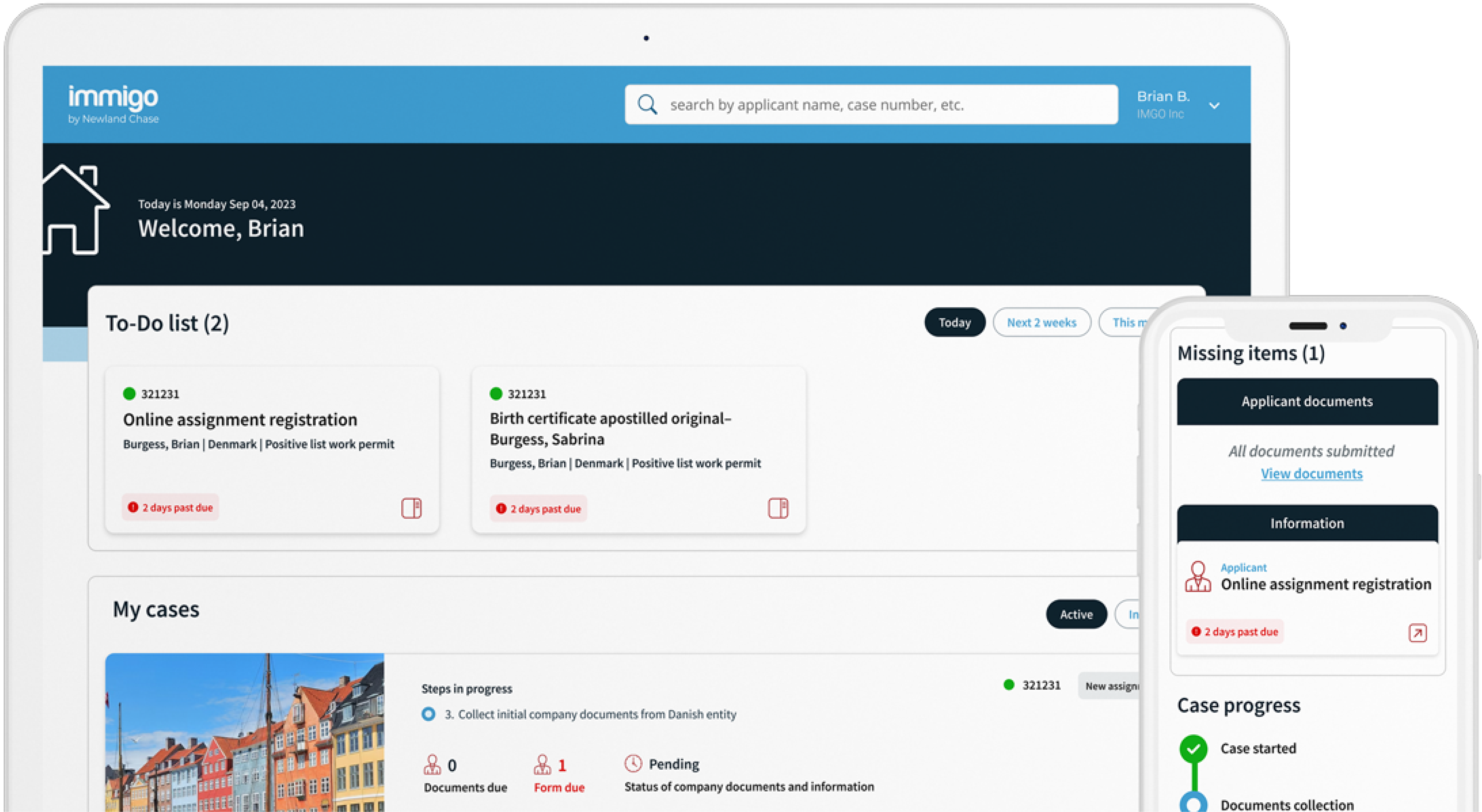

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

Pre-entry English language testing is it fair?

December 20, 2011

We have been closely following the case of R (on the application of Chapti & Ors) v SSHD – interventions by JCWI and Liberty, CO/1183/11435/1141/2010, which was a challenge brought in the High Court of the legality of a certain part of the United Kingdom’s Immigration Rules.

Paragraph 281 of the Rules sets out the requirements which must be met by a person seeking permission to enter the United Kingdom with a view to settlement as the spouse or civil partner of a person present and settled in the United Kingdom, or who is on the same occasion being admitted for settlement. Previously, it had been necessary only for foreign spouses or civil partners to demonstrate sufficient knowledge of life and language in the UK when applying for settlement after 2 years of living here. This requirement remains, as they must still take the Life in the UK test after 2 years in the UK.

However, a new requirement came into effect from 29th November 2011, and paragraph 281(i)(a)(ii) was amended to reflect this. Now, before entering the UK and when lodging their initial application, a spouse or civil partner must provide “an original English language test certificate in speaking and listening from an English language test provider approved by the Secretary of State for these purposes, which clearly shows the applicant’s name and the qualification obtained (which must meet or exceed level A1 of the Common European Framework of Reference).” There are some exceptions to this rule, such as applicants aged over 65 or cases where there are ‘exceptional compassionate circumstances,’ but clearly the majority of applicants will not fall within one of the exemption categories, which are being applied very restrictively.

Therefore, the Government has made it significantly more difficult for spouses or civil partners to gain entry into the UK with a view to settlement, because they must demonstrate a high level of proficiency in the English language before they can enter the country.

We feel that the rule change is unnecessarily harsh, and has been introduced in a way that takes no account of the challenges applicants face in gaining access to the necessary resources. The availability of English languages classes differs massively across the world – in remote rural areas of countries such as India or Africa it will be physically difficult and extremely costly to access English classes. The A1 level required is very high, particularly for applicants who have had little or no chance to learn English previously. Residing in the UK provides the best chance to learn the language, and since spouses or civil partners must also pass an English test after 2 years of living here, it seems unfair not to allow them the chance to develop their speaking skills during those 2 years.

Further, applicants may not have access to a testing centre where they can attain the required certificate from an approved provider. UKBA have admitted that they do not have the requisite centres available yet and we cannot understand why some form of transitional arrangements has not been introduced to compensate for this.

Chapti was a judicial review case brought by several parties to challenge the amendment to Paragraph 281. Mr Chapti was unable to meet the language requirements because of the difficulties of learning English in the rural village where he lived. The other Claimants had similar problems, such as there being no UKBA approved test centre in Yemen, an applicant being illiterate, lack of computer skills or easily accessible English language classes.

Unfortunately, Mr Justice Beaston dismissed all three applications for judicial review. A number of different reasons for this decision were given in his judgment, some of which we have highlighted below:

i) the Rule is justified and rationally connected to the legitimate aims of promoting integration and protecting public services;

ii) whilst there are advantages of learning English in the UK, SSHD was entitled, in the light of the increase in spouses taking the ESOL route, to conclude that the advantages of post entry learning did not outweigh the advantages of having some limited knowledge of language before arrival;

iii) there was some evidence showing that pre-entry acquisition of language would serve as a stepping stone for labour market participation, and other participation in society;

iv) there would be savings for public and health authorities;

v) whilst the costs of acquiring linguistic skills might be problematic for applicants – there are other large costs associated with the same process which have not been considered disproportionate – e.g. the visa application fee of £800, the requirement to maintain and accommodate spouses without state support;

vi) there was no indirect discrimination on grounds of nationality, ethnic origin or disability

However, it has been confirmed that the Claimants, who are supported by Liberty and JCWI (the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants), have been granted leave to appeal. We will be following and commenting on this important case, and invite you to leave your thoughts below.