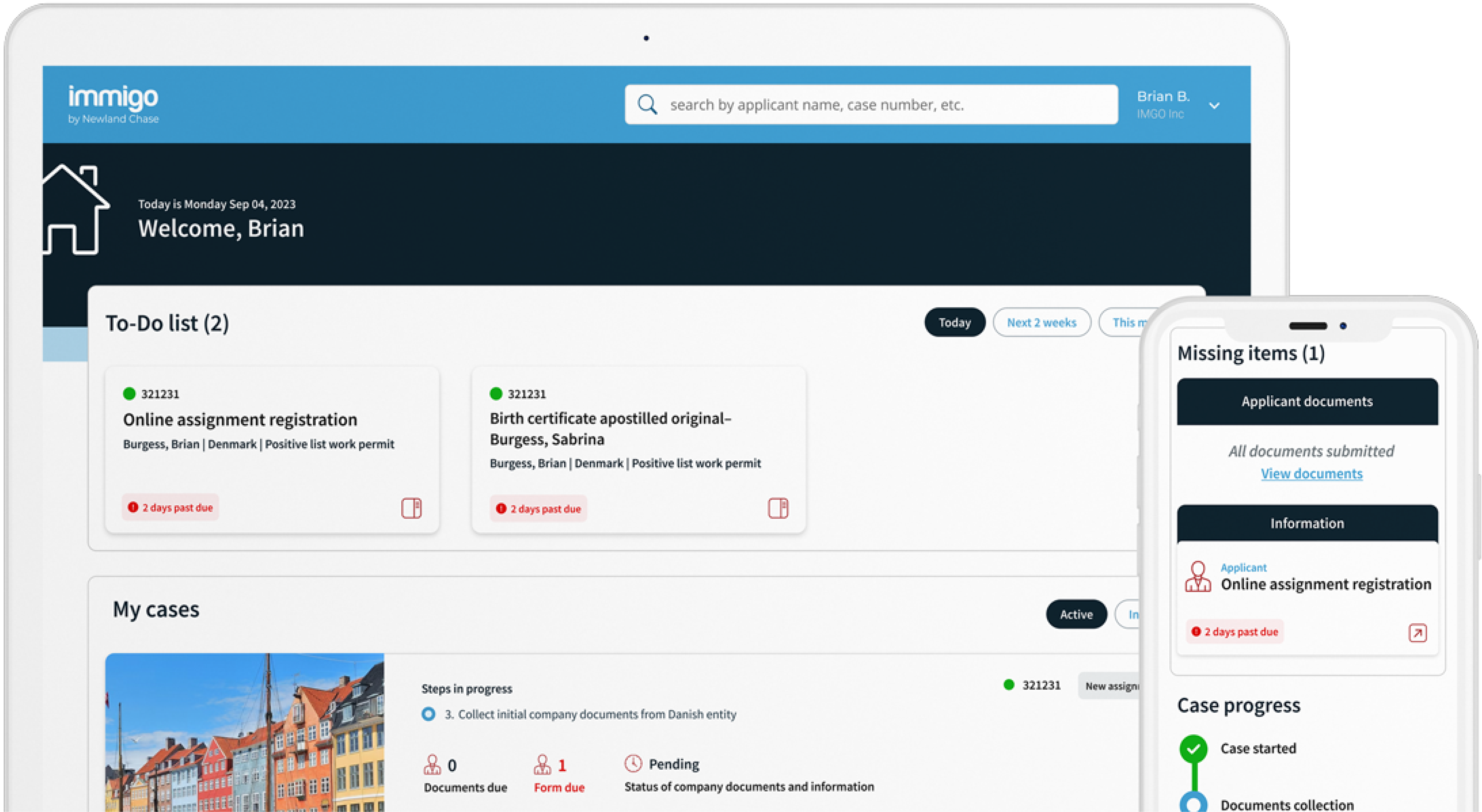

Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

What May be on the horizon for UK Immigration?

April 25, 2012

We haven’t posted for a while due to holidays and important maintenance work on our site, but will now resume blogging as normal and invite you all to comment along with us!

On the 6th April 2012 a series of changes designed by the Government to reduce the numbers of non-EEA foreign nationals working and settling in the UK came into force. We have documented these in the News pages of this site, and further changes are due in June of this year, which include increasing the level of funds applicants under Tiers 1, 2 and 5 of the Points Based System will need to provide evidence of before they can satisfy the maintenance requirement.

However, a leaked cabinet letter sent by the Home Secretary Theresa May to the Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, which was viewed by The Sunday Telegraph last month, has revealed that even more drastic changes to UK immigration could be forthcoming. The suggestions are aimed at reducing the numbers of non-EEA migrants entering the UK on family visas, for example as the foreign spouse of a British citizen.

The letter has received widespread publicity and invoked powerful reactions both for and against the changes suggested by our Home Secretary. Over 2,000 comments were posted on the Sunday Telegraph’s article about the letter, which range from support for the proposals and criticism of immigration in general, to others who argue that couples who are in real, loving relationships should not be subjected to draconian measures and delays of a year or more before they can live together legally.

We have summarised the proposals made by the Home Secretary as follows:

-

A minimum income threshold of £25,700 for a British citizen or person settled in the UK to sponsor the settlement of a spouse or partner.

-

For a partner with one child, the income threshold would be increased to £37,000 per year, for two children to £49,300 and for three children the threshold would be £62,000.

-

The amount of time which must pass before spouses can apply for indefinite leave to remain, to settle permanently in the UK, would increase from two to five years.

-

The level of English a spouse or partner must demonstrate to qualify for settlement would be raised.

But do these changes, as drastic as they may seem, come completely out of the unknown? We do not believe so.

In 2011, the British Government launched a public consultation on family migration which was open for several months. Proposals outlined in the consultation included a new minimum income threshold for sponsors of non-EEA spouses or dependants, and increasing the two year spouse probationary period to five years before spouses and partners can apply for settlement. Thousands of responses were received from all sectors of British society, and according to May’s letter, these responses were largely positive. We wrote a detailed article at the time examining the proposals and highlighting the unduly restrictive nature of some of them.

Alongside this consultation, the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) was asked to report on “what the minimum income threshold should be for sponsoring spouses/partners and dependants in order to ensure that the sponsor can support his/her spouse or civil or other partner and any dependants independently without them becoming a burden on the state.” The threshold at that time stood at £13,700. The MAC concluded in November 2011 that a minimum salary of between £18,600 (which would reduce settlement through the family route by 45%) and £25,700 (reducing settlement by 63%) ought to be implemented.

Clearly, Theresa May has opted to utilise the higher end of the salary scale proposed by MAC in the changes she outlines. We are concerned that this is unnecessary, since MAC indicated a salary of between £18,600 and £25,700 would be sufficient for ensuring that migrant spouses will not be a burden on the UK taxpayer.

The amounts which must be earned should a partner of a British citizen wish to bring his or her children to the UK also seem rather excessive. Finally, the requirement that non-EEA spouses must live in the UK for 5 years before they can become permanent seems unwarranted. Five years is a lengthy period of time to impose on couples, most of whom will be sharing a genuine marriage or relationship, before they can be assured they both have the right to reside in the UK permanently.

Pro-immigration groups have declaimed this ‘crackdown’ as being a political move, and it is hard not to draw some conclusions from the fact that immigration is debated so fiercely by the general public, large sections of whom wish to stop migration into the UK, and the Government’s tough stance against non-EEA migration. But the fact remains that ministers can do nothing to reduce migration from European States due to the rules and regulations on freedom of movement, so we are forced to wonder at the real scope any of these changes could have in reducing net migration.

Instead, we stand to risk alienating British citizens who have a legal right to bring their families here, and valuable skilled non-EEA nationals who will be put off by the UK’s hostile attitude to immigration.